Godsforge Origins and Q&A

By Brendan Stern, 12-10-2022

Details on the making of the board game Godsforge and its expansions.

If you have questions about the rules or otherwise we often check the forums at Board Game Geek if you'd like to post there. Please give us a rating there if you enjoy this game.

While researching game design, I always heard advice that I should playtest my prototypes with strangers instead of with friends. I happened to bring my game, called Etherium Forge at the time, to open game day at Source Comics and Games, a local shop here in Roseville, Minnesota. I sat down to play with Travis Winter, and I had no idea he was an employee for Atlas Games, a publisher responsible for games like Gloom and Once Upon a Time.

After playing a couple games he asked if he could keep the prototype and bring it to their game retreat where they review games for possibly publishing them. Two weeks later, they said they wanted to publish the game. I was pretty excited about this as I was pretty close to the point of either creating this game myself on Kickstarter or finding a publisher. Being new to the board game industry it was an easy choice to work with Atlas, but I really had no idea what I had gotten myself into.

The thing is, I had already spent hundreds of hours on this game prototyping, playing, and designing. However, after they picked the game up, there was still a ton of work to be done. The fun of the game was there, but there were many rough edges, so I was lucky Atlas could work through those with me, ultimately creating a better game.

It was a long road where I learned a lot, and I’m thankful for the experience. It made me much better at designing the expansions while working with Michelle Nephew, co-owner of Atlas Games.

Can you explain your inspiration for the game?

I grew up playing Magic the Gathering and role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons (D&D). When you run D&D, you learn many lessons about game design, like gauging fun, setting up challenges for players, game balance, organization, or improvisation. Justin Gary, creator of the card game Ascension, has a podcast I recommend called Think Like a Game Designer where, not surprisingly, most guests grew up playing D&D and/or Magic.

Godsforge started as a crafting system for D&D where I wanted you to either hunt down materials and turn them into magic items or play a mini game with dice to see if you could magically forge the objects, pulling them right out of the ether. At some point I’ll write an article solely focusing on this.

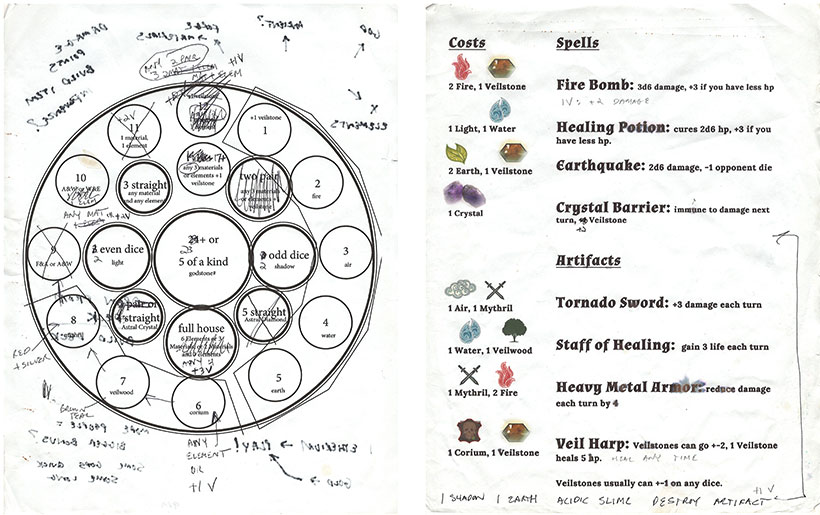

I wanted to test this crafting system with rapid iteration, having players craft items and then somehow use them. This wouldn’t work in a roleplaying game very well because it would take too much time. So I created a small game that was done on a couple pieces of paper with a simple combat system. Looking back, these look like the scribblings of a madman.

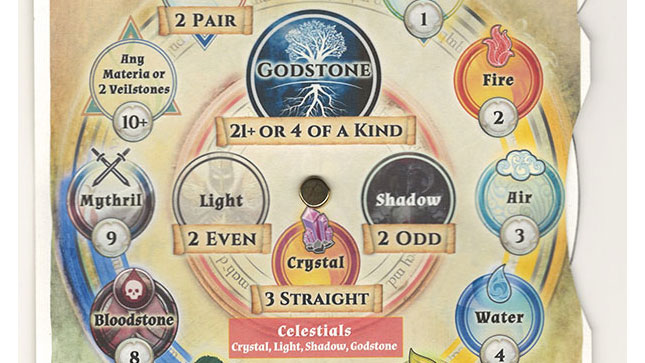

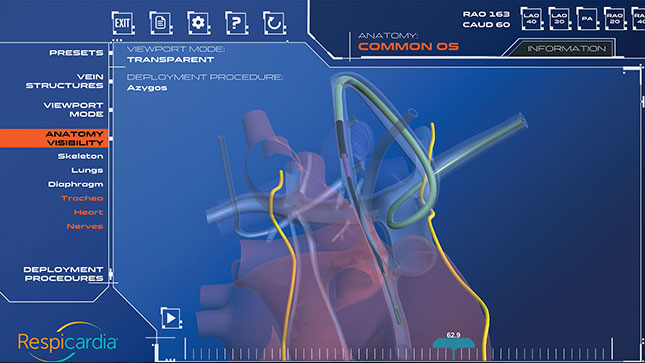

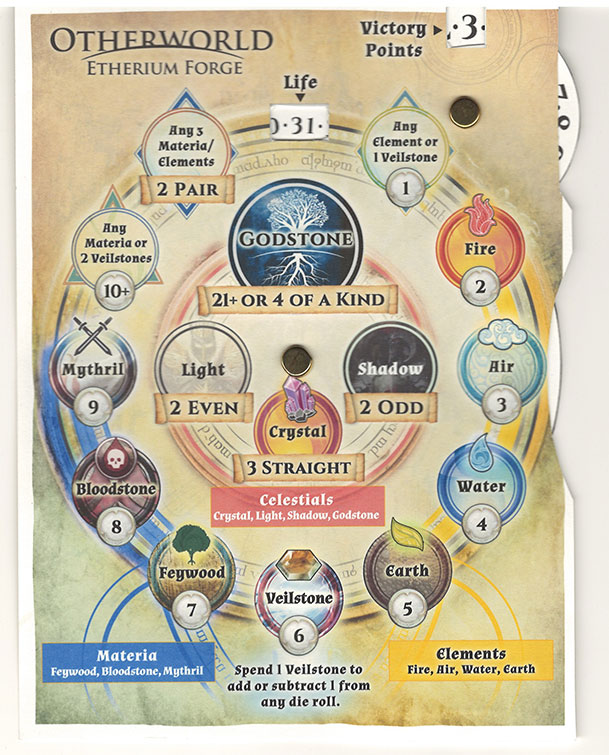

Basically you rolled four dice, compared them to the Etherium Forge, the magic summoning circle, and then looked to see if you had summoned the elements needed to craft an Artifact (later called a Creation) or Spell. You would deal damage to each other until you knocked the other player’s life total to zero.

One of my playtesters said, “This should be its own game.” After more testing, we found it quite fun all by itself, so that was the start of Godsforge.

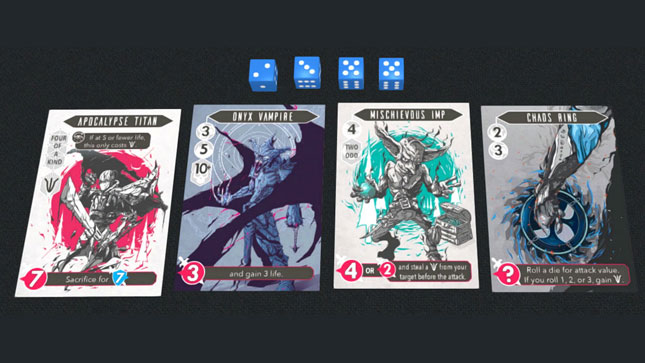

Each ability that could be created was instead moved to cards to easily track them. The Etherium Forge board got developed further into this really cool thing, complete with a life tracker and victory point tracker (when the game had victory points), but then we realized it was completely unnecessary! Instead, we put the numbers directly on the cards making the system simpler, but we lost the cool feeling of using the summoning circle. One mistake we made was leaving the element names on the numbers and keeping them in the rules. This ended up being a bit confusing and upsetting reviewers. In the second edition of the game, the elements in the rules are almost always referred to as numbers.

What games inspired you?

Because this game started as a roleplaying add-on where you craft magic weapons, and where I was only using standard six-sided dice, I researched other games that used similar mechanics. Kingsburg and To Court the King influenced the card playing and crafting of Godsforge, while Magic: the Gathering inspired card effects. 7 Wonders inspired me to create a magic battle game with simultaneous play, something I wasn’t sure existed in the marketplace. This ultimately became one of our biggest game design principles, keep it fast with simultaneous play.

Kingsburg

In Kingsburg I liked how you could roll dice to collect materials that you could then use to upgrade your city. I modified this core loop to remove the multitude of needed components, so instead you only use your current dice roll to upgrade your board state, and instead of city upgrades you are playing cards.

In addition, the Veilstone was inspired by the tokens in Kingsburg because I love the design of being able to shift your dice with a token. It gives the player agency to control the randomness of the dice. I knew I wanted the Veilstone to be plentiful enough so players could always play a card each turn, but I also wanted Veilstones to Empower the abilities of their cards. Then players would have to decide if they wanted Veilstones to help them play cards vs. making their current cards in play more powerful. Another enjoyable part of Veilstones is the ability to save them up for huge Spell effects.

The game To Court the King inspired using Poker style combinations on the cards like Four of a Kind or Three Straight. We created the other costs like Two Even (two even results on the dice) or 10+ (two or more dice adding to 10 or higher) based on what would create a mathematically balanced game allowing you to typically play a card each round.

Magic the Gathering

When I was a teenager, I played a variant of Magic the Gathering with friends where we threw all of our best cards together to create what we called Big Deck. We all drew from it and played a large multiplayer game. However, there were some things I didn’t like about it:

- Early in the game players would be indecisive on who to attack to avoid retribution, making the early game slow.

- Players often ganged up on one player either randomly, out of spite because they took more than their share of pizza or Dew that evening, or to attack the perceived leader. This often led to a player being eliminated from the game early while the others played for a long time, which leads me to……

- Games went really long, sometimes over two hours. This often happened because of multiple options during each turn, board state resets where cards destroyed all Creatures in play, or cards that let you search through the deck.

- There was a lot of down time for each player while waiting for each other player’s turn.

- Because the deck was large, sometimes players would only draw mana generation or defensive cards, due to the shuffle, creating stagnant play.

Inspired by these issues I wondered how I could make a game similar in feel to Magic, but ultimately very different.

- Making players all attack to their left immediately gets combat going, and there is less hard feelings about it. This also reduces, but does not eliminate, targeting a player which keeps all players in the game longer. The best way to target other players in Godsforge is with cards that can damage any player, or destroy or steal-a-card effects. There are some really fun cards that do this in the expansions.

- Making play simultaneous to keep things moving and reducing wait time.

- Removed effects that took too long to perform, reset the board, search the deck, or disrupted simultaneous play.

- Created the dice rolling mechanism to play your cards. This keeps the cards in the deck and the card cost/mana system separate, similar to Hearthstone. This is better at allowing you to play your cards.

- Balanced the deck between attack, defense, and Veilstone generation.

Godsforge was born as a 3+ player game and we playtested mostly at 3-5 players. The game is a decent dueling game, 1 vs. 1, but it is certainly much simpler than other dueling games. We even played 7-8 player games with two copies. Suprisingly they went well, but they get pretty chaotic. Now that you can play with six players if you have both expansions, the games can get pretty wild, but they still can be done relatively quickly.

"I was very, very impressed with Godsforge. The designer clearly understood what makes the genre work and where improvement areas were, and he capitalized on all of it."

-Demetri Ballas

Godsforge is medium to lightweight on complexity. What made you want a simpler game?

A lot of it was shooting for what I thought the market might want, a multiplayer battle game that could feel epic in about 30 minutes. Atlas initially tried some prototypes that were more complicated, but we pulled it back. We continually hit this game with the simplification hammer. I had to learn to “kill my darlings” or toss out pieces of the game I really liked.

- I loved the initial board with the Etherium Forge (above), but it had to go. It was an unneeded step in playing your cards.

- For a long time we had a communal card in the middle of the table called the Otherworld Card. It sat face up, and anyone could bid to play it. It was fun, but ultimately it added too many rules and components for what it was worth, so we tossed it out.

- We had victory points early in the process as an alternate way to win the game rather than fighting it out. Again, it was fun and interesting, but it made the game more complicated, and sometimes felt strange when this huge chaotic battle was going down and then it suddenly ended due to one player crafting specific cards.

- You can’t go over 30 life in Godsforge. I didn’t want to have this life cap, but it ended up being a good decision because it keeps the games from going too long and it keeps people in striking distance for the end game.

How did you come up with the name of the game?

The game was originally called Etherium Forge, but I wasn’t satisfied with it mainly because nobody knows what Etherium is. We tried over 75 alternate names, polling players, and it was a bit exhausting. I mentioned to the production manager “I am open to new theme ideas… Are the players clan leaders or are they gods, wielding the Godsforge?” She picked this out later and suggested using it. I was reluctant because people might think it is God’s Forge and it sounds a bit religious. Ultimately this is the name that stuck, and it is fitting since these powerful forges give people the power of gods.How did you choose the artist for godsforge?

We had ideas of using an art nouveau style for Creations and geometric art for Spells early on, largely developed by the production manager. As I understand it, Atlas got a reference for an artist named Diego Rodriguez. However, they ended up talking to a different artist with the same name! It turned out to be a great mistake, since the art of the game has received a lot of praise and gave it a unique feel.

My prototype art was purchased stock imagery.

Who do you envision playing this game? Who is the target audience?

This game is good for people who want an epic, multiplayer, simultaneous, fantasy battle game that can be played in around 30 minutes. It has a fair amount of luck, but a good tactical player can significantly increase their odds of success, similar to games like Poker or Hearthstone Battlegrounds. If you like Battlegrounds like I do, I highly recommend Godsforge. They are both high variance, but ultimately satisfying when you can put together a winning board. I wrote a strategy guide if you want an edge on your opponents.

I have seen a lot of young teenagers love this game, playing it over and over again. Some of the appeal is how simple the game is. There is so much less text, which lowers the barrier for parents to play with their kids. The rulebook is much smaller than Magic's or many other board games these days. I can usually teach the game in 5-10 minutes.

Also, kids love throwing big Fireballs.

How did you come up with the card costs? What is the math behind it?

I love the math behind the Forge Roll in Godsforge. It was made to obscure what your exact odds are at playing a card, because in the theme of crafting a magic item or spell, I didn’t want the odds easy to nail down. I wanted it a bit more chaotic.

I had four people work on figuring out the odds of playing each card, and how the odds are affected when you have one or more Veilstones. We found out, in our best estimation, that this couldn’t be done with a straight math problem, but instead had to be calculated with a simulator for a best guess estimate, with pretty decent accuracy. We ended up creating two independent simulators and comparing their results. If you are good at math, perhaps you know a formula that could solve the Forge Roll of Godsforge. If so, please contact me or leave a comment below.

We found out that some cards could be played around 95% of the time and others about 20% of the time when you had no Veilstones and you rerolled very aggressively (it was a computer sim, so it maximized rerolls). The cards averaged around 70%-80% playability. The beauty behind this is when you have four options, each with an estimated playability of about 75%, it takes your odds of not playing a card down to less than 1%. So you will typically be able to play a card, but keep in mind, some cards in the game cannot be played at all unless you have one or more Veilstones, so their probability in the above scenario is 0%. If you have those in your hand with no Veilstones you are significantly increasing your odds of not playing a card. Also, if your card costs are similar, you are also reducing your chances of playing a card, so often it can be a good play to discard cards with similar costs.

When you have Veilstones, which allow you to add or subtract one on any one die, they dramatically increase your odds of playing a card. I forget the odds now since we did this back in 2015, but I believe it was close to a 15-25% boost in making each card more playable. Having two Veilstones really increases your odds, and it wasn’t a flat 15-25% for each one, but if I remember correctly, it was exponential. But I was certainly okay with this, because Veilstones take work to acquire.

The Forge Roll is an efficiency and press-your-luck game. You want to roll and reroll to spend as little Veilstones as possible while playing your best card for either the early, middle, or late game and you need to ensure you can still play a card after your rerolls. See the strategy guide for hints on which cards are best at different times of the game.

I’ve seen reviewers say, “I can always play a card! It is so easy!” Yes, we designed it this way, at least 99.5% of the time depending on your hand.

However, one reviewer said, “I can always play the best card or the second best card.” This is objectively incorrect unless you’ve saved up some Veilstones which takes work to acquire. It is still a matter of how efficient you can play your cards with rerolls.

Do you have any amusing anecdotes while creating or playtesting it?

It is possible I may have thrown the game when playing Travis Winter in our first game of Etherium Forge. Don’t tell him. He’ll never read this thing on the internet.

When playtesting with Adam Biessener, formerly Senior Associate Editor at Game Informer, he gave me a list of around 7 major items to change with the game. I didn’t want to make these changes, but I believe I made almost all of them. It was a very helpful playtest.

When playtesting with Adam Rehberg of Adam's Apple Games (now with the hugely popular hit Planet Unknown), he helped me decide to remove the Otherworld Card mentioned above. I also had some input on his game Swordcrafters.

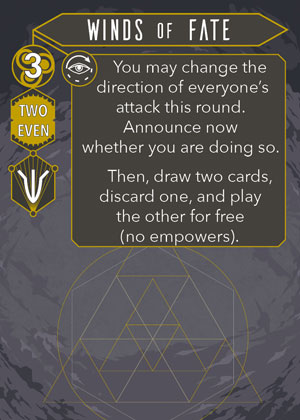

One of my favorite memories while playing is when one player flung a huge Fireball at his opponent, but then a young teen played Winds of Fate, which reversed the attack order and the Fireball got sent towards me instead. He was so excited at this result, eliminating the creator of the game! Moments like this with high fiero, or a feeling of emotional elation after a huge discovery or victory, are my favorite thing to see.

What advice would you give to other new game designers?

Other great game designers have laid down good game design principals that I'll repeat here.

- The best advice I can give is to focus on the fun of your game and to cut anything that doesn't contribute to that, find what makes it unique, and define your target audience and playtest with them as much as possible.

- Play with other game designers. You will get more advanced feedback that will propel your game forward quicker. Find their game meetups and play their games, and listen to their feedback when they play yours.

- Also play with complete noobs. They will make your game more usable and help the User Experience.

- Listen to podcasts like Ludology while you mow your lawn.

- Listen to the problems or frustrations of playtesters closer than their solutions. Also focus on their non-verbal cues. In a new game I’m making, one player kept their cards face up on the table because nine cards in hard was too much. This indicates to me to consider lowering the hand size.

- Make a set of rules that is as short as possible that can still give players agency, options, and creative play.

- Focus on creating a fun engine rather than specifically a board game.